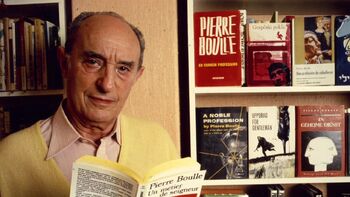

Pierre François Marie Louis Boulle was a French novelist born in Avignon, France. Pierre and his sisters Suzanne and Madeleine were the children of Eugène Boulle, an eccentric lawyer who wrote theatre reviews in a local newspaper and married Thérèse Seguin, the daughter of the papers editor, but died of heart disease in 1926. Pierre studied at the Sorbonne and the Ecole Supérieure d'Electricité de Paris, graduating with a degree in electrical engineering in 1933 and subsequently became an engineer, but in 1938 he moved to Malaya, where he worked as an overseer on a rubber plantation just outside Kuala Lumpur. In 1939, at the outbreak of war, he joined the French army in South-East Asia and after German troops occupied France he joined de Gaulle's Free French resistance movement in Singapore, where he received training as a spy and saboteur. He became a secret agent operating across China, Burma (now Myanmar) and French Indochina (now Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam) under the unlikely alias of 'Peter John Rule' - a Mauritius-born Englishman. It was in that guise that he was captured by Vichy France loyalists in 1943, floating down the Mekong River in a bamboo raft. Imprisoned in Saigon, he was sentenced to hard labour for life before escaping in 1944 and joining the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) - the forerunner of the modern SAS - in the Indian city of Calcutta (now Kolkata). He was later made a chevalier of the 'Légion d'Honneur' and decorated with the 'Croix de Guerre' and the 'Médaille de la Résistance' by General de Gaulle. He described his war experiences in the non-fiction book Aux sources de la rivière Kwaï (1966, 'My Own River Kwai').

Boulle's wartime experiences would also colour virtually everything he produced in the fiction writing career he pursued after the war. But they made their most immediate impact in the novel he published in 1952, Le Pont de la rivière Kwaï, which was translated into English (by fellow ex-SOE agent Xan Fielding) as The Bridge over the River Kwai, and later adapted into the 1957 film by Columbia Pictures known as The Bridge on the River Kwai with Alec Guinness and William Holden. It tells the story of a group of British PoWs forced to build a railway bridge by the Japanese. In the film, the bridge is blown up, a fact that differs from Boulle's version. "For three years, I fought them over this change," he wrote later. "In the end, I gave up. Now, I don't bother. I just take the money and shrug." He received an Academy Award for scripting the novel into film despite not having written the screenplay and, by his own admission, not even speaking English - he had been credited with the screenplay because the film's actual writers, Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, had been blacklisted as communist sympathizers. Boulle supposedly gave the shortest acceptance speech in the history of the Academy Awards, simply saying "Merçi", but other sources maintain he was not even present at the awards ceremony, with Kim Novak accepting the award on his behalf. The Motion Picture Academy added Foreman's and Wilson's names to the award in 1984. [1]

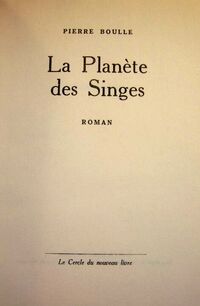

Title page of first edition

Boulle wrote both William Conrad - his first novel - and Le Pont de la rivière Kwaï while he was still living in Malaya, having returned to work in the rubber industry. After he returned to France a disillusioned ex-patriot in 1949, he began writing moral fables to contrast his profound experience in the Orient with those absurdities of life he found in France. Three of his books, Contes de l'absurde (1953), E=mc2 (1957) and Le jardin de Kanashima (1964, 'Garden on the Moon', concerning the use of Hitler's engineers in the U.S.-Soviet space race and the grim determination of the Japanese to out-pace both[2]), took to task his distress about science and man's over-dependence on machines. They have been all classified as works of science fiction, but Boulle rejected that label, preferring to call his works social fantasy. Boulle's other works include La face (1956, 'Saving Face' / 'Face Of A Hero'), L’épreuve des hommes blancs (1957, 'The Test'), and Un métier de seigneur (1960, 'A Noble Profession', partly based on Boulle's experience as a secret agent during World War II). However, in the realms of science fiction, Boulle is mostly remembered for penning the 1963 novel, La Planète des singes. Boulle didn't see his novel - a witty, philosophical tale belonging properly with Karel Čapek's R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), and other social satires of the day - in terms of contemporary sci-fi; he wasn't really interested in writing a science fiction novel, but to get his characters from the Earth to his imaginary world, he relied on space travel and Einstein's relativity theory: "It is a story, and science fiction is only the pretext. I wouldn't even know how to define SF...I think it's the genre where you can deal with and imagine unhuman characters, but in my book my apes are men, there is no doubt. I believe it was triggered by a visit to the zoo where I watched the gorillas. I was impressed by their human-like expressions. It led me to dwell upon and imagine relationships between humans and apes." The novel was translated into English by Xan Fielding as Monkey Planet in the UK a year later (Fielding was responsible for translating many of Boulle's novels into English). Abridged versions (titled Planet Of The Apes) were included in Saga: The Magazine For Men (May 1964) and Bizarre Mystery Magazine (November 1965) with some illustrations.

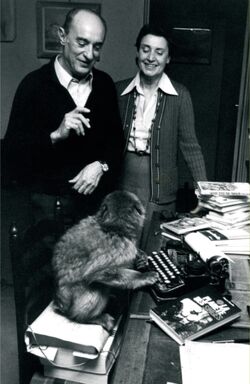

Arthur P. Jacobs and Pierre Boulle

But, even before its UK publication, it had found its way to Hollywood where Twilight Zone screenwriter Rod Serling had been hired in late 1963 to adapt it for the cinema by 'King Brothers Productions'. By April 1964 the screen rights had changed hands, but new producer Arthur P. Jacobs' 'APJAC Productions' struggled to raise the necessary finance. Serling also struggled - with the task of adapting this complex story for the big screen - and submitted a final draft in March 1965, having already added the iconic 'Statue of Liberty' ending. For the next two years, Jacobs worked to raise enough funding for what had developed into a very expensive project. Before filming began, another experienced writer, Michael Wilson, screenwriter on The Bridge on the River Kwai, was brought in to work on the script. Wilson had written many excellent film scripts (including It's A Wonderful Life and A Place in the Sun) - some, such as ..Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia uncredited until much later due to the blacklisting of the McCarthy era.[3] Private correspondence reveals that Jacobs continued to consult with Pierre Boulle during the screenwriting process. Boulle approved of some of the changes made to his story, but not of the 'Statue' ending nor the final dialogue as written by Wilson. Boulle’s suggestion of a stark and almost wordless final reveal was adapted into a subsequent re-write, and was further refined by actor Charlton Heston.[4] Finally, in early 1968, Boulle's novel was released by 20th Century Fox as their feature film Planet of the Apes. The film version of Boulle's story differed greatly from La Planète des singes, although each maintained the same thematic elements of a dystopian future where apes evolved from man.

Boulle maintained an indifferent and occasionally dismissive attitude towards the cinematic version of his book throughout the rest of his life. He was invited to the Paris premier of the movie but declined, excusing himself to help his niece with her school studies. In its allusions to the racial tensions of US society and its use of the quintessentially American Statue of Liberty, Boulle seemed to feel the story had lost some of its relevance to the human race as a whole.[4] Interestingly, he also didn't regard his novel very highly (at least, in comparison to his other works) and didn't believe that it would make a great feature: "To speak frankly, I don't consider [La Planète des singes] one of my best novels. For me, it was just a pleasant fantasy. There are lengthy parts of the novel where I was not completely satisfied. I never thought it could be made into a film. It seemed to me too difficult, and there was the chance that it would appear ridiculous. When I first saw the film nothing was ridiculous because it had been very well made. In comparison to the book, there were a lot of changes made. Some of them were disconcerting. The first part of the film was very good, and the makeup of the apes was particularly good, and, as I've said, that could have been ridiculous, but it wasn't. I disliked somewhat, the ending that was used - the Statue of Liberty - which the critics seemed to like, but personally, I prefer my own. Since they decided to make the film, they picked this ending. They had that final scene in mind from the first day. I knew they wanted to do it from the beginning. Arthur Jacobs had talked with me about it, and finally I said, 'let's try it, then'. The critics seemed to approve of the change." According to Jacobs, Boulle wished he had thought of the famous ending of the film: "I sent the finished script to Boulle, and he wrote back, saying he thought it was more inventive than his own ending, and wished that he had thought of it when he wrote the book." [5] This quote is, however, in keeping with Jacobs' tendency to embellish the truth for the sake of publicity.[4]

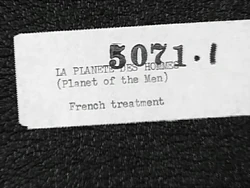

Boulle was asked to submit a treatment for a sequel to the successful movie. Titled Planet of the Men, it featured a messianic Taylor 14 years after the events of Planet of the Apes. It involved an uprising against the apes, following which they reverted back to their primal states. "After the success of the original film, Arthur Jacobs requested that I do a sequel for him. They accepted the treatment that I worked on, but they made so many changes that very few of my ideas were left. It was completely different from what they finally used on the screen. I used the end of the first film as my starting point. Taylor realized that man still existed but had regressed to a primitive and savage existence. He decides to attempt to retrain and educate them to bring them back to a normal life. He teaches them the use of language. The apes consider this a great danger and a terrible war begins. Many of the sub-humans contest Taylor's leadership because he wants to make peace, and in the end they win out and destroy all of the apes whom they greatly outnumber. I relate this very badly because I have forgotten it." Boulle found the experience much less enjoyable than writing a novel, and attempted to write from the visual perspective necessary for screen-writing: "It was an interesting and amusing experience for me, nothing more. It's not the same. When I was writing I was thinking in visual terms, picturing the actors, Charlton Heston, and the others. I played the game, but my film was never made, and I don't even want to publish it, and it never will be." Jacobs declined to use the treatment (the English-language copy of which is dated July 22, 1968), preferring to employ Paul Dehn (another ex-SOE agent) to script Beneath the Planet of the Apes: "We didn't plan any sequel in the first one, but it became so successful that Fox said you must do a sequel, if you can come up with one. First I went to Pierre Boulle to write the screenplay. He said he didn't know how one makes one, then when I showed him a print of the first one, he was just absolutely ecstatic. He DID write a treatment for a sequel, titled 'Planet of the Men', but it wasn't cinematic. Then, I went to Paul Dehn and Mort Abrahams in London, and spent about two weeks, walking and walking, trying to figure out where to go from the Statue of Liberty."[5]

Boulle took no further part in developing the Planet of the Apes franchise he had unwittingly created and showed little interest in the Hollywood phenomenon it became, though he continued to receive credit for creating the concept and characters through the various sequels and spin-off media. "I haven't seen the second or the third film. I did read the script for Beneath the Planet of the Apes, but it doesn't interest me because it's no longer my work. It's something totally different. The cinema means nothing to me now. I never go to see films. When I was younger I used to go to films often, but not any longer. A lot of my books are going to be made as films, but for now, there are only two that have been and I don't have to complain about them." [5] Other of Boulle's works have indeed been adapted for film and TV, including two episodes of US drama anthology series Playhouse 90: 'Not the Glory' (1958, based on 'William Conrad') and 'Face of a Hero' (1959, based on 'La Face' and starring James Gregory), Porträt eines Helden (1966, West German TV film based on 'La Face'), William Conrad (1973, French TV film), Le point de mire / Focal Point (1977, French film based on 'Le Photographe'), The Miracle (1985, US TV film based on 'Le Miracle' from the collection 'E=mc2'), Un Métier de Seigneur (1986, French TV film), and a forthcoming (2015) film adaptation of A Noble Profession ('Un Métier de Seigneur').

In 1976, Boulle received the Grand Prize of the Société des gens de lettres for his contribution to French literature. Pierre Boulle died in Paris on 30 January 1994, at the age of 81. He was cremated and his urn placed in box 40 598 of the columbarium of the famous Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris before, in 2002, being transferred to the family vault in the cemetery at Saint-Veran, Avignon. Following a relationship with a separated Frenchwoman in Malaya before the war, Boulle remained unmarried. After moving to Paris he lived first in the Quartier Latin and then with his widowed sister, Madeleine Perrusset, whose daughter, Françoise, Pierre helped raise and at one point planned to officially adopt. Five years after Pierre's death, Françoise and her husband Jean Loriot discovered unpublished manuscripts, resulting in a new novel in 2005 - L'Archéologue et le mystère de Néfertiti ('The Archaeologist and the Mystery of Nefertiti', probably written between 1949 and 1951) - as well as a collection of unpublished short stories in 2007 - L’Enlèvement de l’Obélisque ('The Missing Obelisk'). Boulle's manuscripts are now housed at the National Library of France.

Notes[]

- Writer Yann Quero suggests that Boulle was strongly influenced by his time in South-East Asia when writing La Planète des Singes. Boulle described in his autobiographical Le Sacrilège Malais (1951) the distinction he perceived between the three principal ethnic groups in inter-war Malaya: the Tamil manual workers, the business-minded Chinese and the passive Malays. He furthermore will have encountered the Hindu caste system among the ethnic-Indian Tamils on the rubber plantation. The dense jungles of the region may have inspired the heavy vegetation described on the planet Soror. In Le Pont de la rivière Kwaï both the Japanese and the British describe each other as 'monkeys' as a term of abuse. He may also have been aware the story of Fr Teilhard de Chardin, a priest who attempted to reconcile evolutionary evidence with Roman Catholic theology but who was consequently condemned for heresy by his superiors and effectively sent into exile in inter-war China.[6]

External Links[]

Pierre Boulle at the Internet Movie Database

Pierre Boulle at the Internet Movie Database- Les amis de l'œuvre de Pierre Boulle (Friends of Pierre Boulle's work)

- Pierre Boulle, el autor de El Planeta de los Simios (biography, in Spanish)

- Pierre BOULLE (1912-1994), écrivain, né en Avignon (Vaucluse) (biography and genealogy, in French)

- Cinefantastique interview, 1972, at Hunter's Planet of the Apes Archive

References[]

- ↑ 'Planet of the Apes - It's the Hollywood remake of a 1960s sci-fi' (2001)

- ↑ The Kamikosmonaut - TIME Magazine (Feb 26, 1965)

- ↑ The Planet of the Apes Chronicles by Paul A. Woods (Page 39)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 The Making of Planet of the Apes, by J.W. Rinzler (2018)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 'Cinefantastique Planet of the Apes Issue' (1972) at Hunter's Planet of the Apes Archive

- ↑ L’influence de l’Asie sur les écrits de science-fiction de Pierre Boulle (The influence of Asia on the science fiction writings of Pierre Boulle) - Revue d’études sur la science-fiction (June 2015, French language)